- Introduction to Yinka Shonibare

- Yinka Shonibare Biography

- Yinka Shonibare CV

- England and Nigeria Today

- Batik- Dutch wax fabric

- Batik as a wax resist

- Heather Gatt

- Nigeria timeline

- Colonization of nigeria

- Resources of Nigeria

- Royal Niger Trading Co.

- Young British Artists

- Gillian Wearing

- Tracey Emin

- Aristocracy

- Aristocratic revolt in France

- Beheading and Marie Antoinette

- Lucid Decapitation

- Mike the Headless Chicken

- Yinka Shonibare ArtHistory.com Biography

- Interview with Anthony Downey for BOMB Magazine

- Synopsis of Swan Lake

- Yinka Shonibare and the Art of Resistance

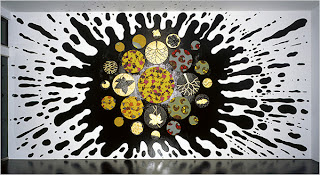

- Work by Yinka Shonibare

- The Dandy

- Albert Camus on Dandyism

- Carlos Esparataco on Dandysim

- Colin Hambrook and Joe McConnell repsond to Yinka Shonibare

- Disabled Artist- Stephan Wiltshire

- Disabled Artist- Alice Schonfield

- Disabled Artist- Matt Sesow

- Disabled Artist- Ping Lian Yeak

- Interview for crossing borders

- Reflective Summary

Monday, May 6, 2013

Table of Contents

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Reflective Summary

Yinka Shonibare is a remarkable artist who uses historical and modern ideas to create aesthetically interesting works of art. He creates tableaus that often reference historical works of art. He uses these classical allusions to add depth of meaning to his work. Yink Shonibare makes his work relevant to modern society by exploring the themes of colonization and aristocracy. These issues relate to the modern day situation of post-coloinzation Nigeria, as well as the vast separation of wealth in society. More recently, his work has become more performance based. I feel that this is a natural progression for his work. He started his practice by creating scenes to photograph, then moved to displaying the scenes. Now, Yinka Shonibare uses the scenes in motion in order to convey more information through his work.

Over the course of this research project, I explored the ideas of headlessness, Dandyism, Aristocracy, Nigerian history, YBA's. I also learned about batik fabric, and disabled artists. This exploration has expanded my knowledge significantly on Nigeria and England. This opportunity to explore new subjects will impact my in practice in positive ways. I have begun to use colors reminiscent of Yinka Shonibare's batik fabric. I am also seeing increased value in three dimensional work. After seeing the natural progression of Yinka Shonibare's work, I am contemplating the possibility of purifying my practice. Yinka Shonibare is able to remove distractions and unnecessary components of his work by showing the essence of what he is trying to say.

Over the course of this research project, I explored the ideas of headlessness, Dandyism, Aristocracy, Nigerian history, YBA's. I also learned about batik fabric, and disabled artists. This exploration has expanded my knowledge significantly on Nigeria and England. This opportunity to explore new subjects will impact my in practice in positive ways. I have begun to use colors reminiscent of Yinka Shonibare's batik fabric. I am also seeing increased value in three dimensional work. After seeing the natural progression of Yinka Shonibare's work, I am contemplating the possibility of purifying my practice. Yinka Shonibare is able to remove distractions and unnecessary components of his work by showing the essence of what he is trying to say.

Interview for crossing borders

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/crossingborders/interview/yinka_interview.html

In this interview Yinka Shonibare explains how his Nigerian and English bi-cultural background has informed his practice. He discusses the key themes he explores including global issues and the question of identity in today's world. He explains in detail the ideas conveyed though his sculpture, The Reverend on ice, 2005 and his film Un ballo in maschero, 2004. The artist's fascination for costume, patterned fabrics, art history and the concept of the dandy are also discussed in relation to his work.

In this interview Yinka Shonibare explains how his Nigerian and English bi-cultural background has informed his practice. He discusses the key themes he explores including global issues and the question of identity in today's world. He explains in detail the ideas conveyed though his sculpture, The Reverend on ice, 2005 and his film Un ballo in maschero, 2004. The artist's fascination for costume, patterned fabrics, art history and the concept of the dandy are also discussed in relation to his work.

Saturday, May 4, 2013

Disabled Artist- Ping Lian Yeak

Ping Lian Yeak

Disability: Autistic SavantPing Lian is an autistic savant who has been producing amazing art since his childhood. He is now fifteen. More of his amazing art may be viewed at his website.

http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2010/03/the-amazing-art-of-disabled-artists/

Disabled Artist- Matt Sesow

Matt Sesow

Disability: Missing a handJust six years after losing his hand as a child in an accident in which a crashed plane severed his arm and took away his dominant hand, Sesow played for the US team in the disabled Olympics in England. While working at IBM as a software engineer, he began painting scenes in oils that were influenced by his traumatic injury.

http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2010/03/the-amazing-art-of-disabled-artists/

Disabled Artist- Alice Schonfield

Alice Schonfield

Disability: Diminished capacity through multiple strokesAlthough Alice Schonfeld is most known for her sculpting work primarily in Italian marble, she is also regarded as an inspirational figure for the disabled community. She has shown a considerable tenacity to work through debilitating illnesses and has done a lot to promote awareness of disable artists. She resides in California.

Disabled artist- Stephan Wiltshire

Stephen Wiltshire

Disability: Autistic SavantWiltshire was born in 1974 in London to West Indian parents. He is an autistic savant and world famous architectural artist. He learned to speak at the age of nine, and at the age of ten began drawing detailed sketches of London landmarks. While he has created many prodigious works of art, his most recent was a eighteen foot wide panoramic landscape of the skyline of New York City, after only viewing it once during a twenty minute helicopter ride.

Colin Hambrook and Joe McConnell respond to a talk by Yinka Shonibare at Shape's launch of the Adam Reynolds bursary

The Adam Reynolds Memorial Bursary was launched at the Camden Arts Centre in

July 2007. The bursary offers disabled or Deaf visual artists a £5,000

award and a year-long artistic residency. In the first year, this will

be hosted by Camden Arts Centre, where Adam himself had a residency at a

pivotal time in his career. The bursary is in memory of Adam Reynolds,

who died in 2005. Adam was a Chairman on Shape's Board of Trustees, a

renowned sculptor and an activist for disability equality in the arts.

Yinka Shonibare opened the event with a few of his own memories of Adam from the time when Shonibare worked as an Arts Officer for Shape. He talked with affection of Adam's supportiveness and eloquence, and in particular his passion for artist-run projects, such as the Adam Gallery, which he set up in 1984. It was unique in that it made the brave move to bypass curatorial and commercial precedents and to put the creative process firmly in the hands of the artist. These ideas rubbed off on Shonibare, setting him on the road to increasingly complex and involved collaborations through a range of media that includes sculpture, painting, photography, film and installation.

Although not a member of the Disability Arts movement, Shonibare readily acknowledges physical disability as part of his identity but creates work in which this is just one strand of a far richer weave. “Historically the people who made huge, unbroken modernist paintings were middle-class white American men. I don't have that physique; I can't make that work. So I fragmented it, in a way which made it both physically manageable and emphasizes the political critique”.(Conversation with Nancy Hynes cited in www.findarticles.com).

Shonibare's prolific work embraces a wide range of themes: identity, history, global politics … most often with a wickedly refreshing sense of humour which makes issues raised hit home all the harder. One of his starting points was a reaction to being questioned by college tutors, as to why an African artist should be interested in making work about Perestroika. This led to a whole chain of work questioning what people meant by African and European. He began with the idea of using fabric as a metaphor. Struck by the fact that batik cloth on sale in Brixton was actually manufactured in Holland, he realised that even the origins of the fabric speak of the inequities of global trade. This led the way to Double Dutch (1994) - a series of small paintings using motifs from batik cloth.

In an age when so many of us feel that buying Fairtrade coffee is doing our bit to rebalance global inequalities, much of Shonibare's work highlights the complexity and complicity which connects the materially advanced countries to the so-called third world. The richly patterned batik-based costumes adorning the headless figures in many of Shonibare's installations reference colonial exploitation, both past and present. Traditional motifs are interwoven with Gucci-style prints, in a way that is both entertaining and subversive. Describing his work as "soft politics", the beauty of the objects in themselves becomes part of the challenge to the status quo. Yinka Shonibare and Rachel Gadsden are among the surprisingly small group of disabled artists who have critically engaged with the issues of war in the contemporary world.

His work contains frequent references to English history. His art historical tableaux such as Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (after Gainsborough) and The Swing (after Fragonard), re-stage images of the aristocracy. Aside from taking a post-colonial swipe they ask questions about the current state of power relations in the world. Who are the anonymous heads behind big corporations who control so much of our lives and aspirations? Gallantry and Criminal Conversation (2002) and Scramble for Africa (2003) are more literal in their condemnation for the power relationships and global inequality forged by the ruling classes of Europe.

Inspired by A Rake's Progress by Hogarth, Shonibare's Diary of a Dandy consists of a series of photographic tableaux, putting himself in the frame. The work, which was on show on billboards on the London Underground during the early '90s, reflects the saccharine obsession for the costume drama, reflecting an idealised past. At the same time by placing himself as a Black, disabled, British man in the centre of the narrative, he questions the aspiration of wanting to achieve a position of power and affluence in contemporary society.

As he talked through his body of work, he talked occasionally but poignantly about his identity as a disabled man. Dorian Gray (2001) explores issues of disability and dandyism, beautifully illustrating Oscar Wilde's parable about the dangers of a society obsessed with the desire for perfection. Coming from a need to break out of the isolation of being alone in the studio, the work is also about the need to work in collaboration. More subtly it reflects a fear of being corrupted by a society steeped in hypocrisy, and the irony of having been launched as a foremost contemporary British artist by Charles Saatchi, engineer behind the Thatcher phenomenon.

The Adam Reynolds Bursary is unique in its aim to provide an opportunity for artists to develop their ideas and practice without pressure to deliver a particular outcome. The successful artist will be selected from an open submission, on the strength of their work and proposal.

Yinka Shonibare opened the event with a few of his own memories of Adam from the time when Shonibare worked as an Arts Officer for Shape. He talked with affection of Adam's supportiveness and eloquence, and in particular his passion for artist-run projects, such as the Adam Gallery, which he set up in 1984. It was unique in that it made the brave move to bypass curatorial and commercial precedents and to put the creative process firmly in the hands of the artist. These ideas rubbed off on Shonibare, setting him on the road to increasingly complex and involved collaborations through a range of media that includes sculpture, painting, photography, film and installation.

Although not a member of the Disability Arts movement, Shonibare readily acknowledges physical disability as part of his identity but creates work in which this is just one strand of a far richer weave. “Historically the people who made huge, unbroken modernist paintings were middle-class white American men. I don't have that physique; I can't make that work. So I fragmented it, in a way which made it both physically manageable and emphasizes the political critique”.(Conversation with Nancy Hynes cited in www.findarticles.com).

Shonibare's prolific work embraces a wide range of themes: identity, history, global politics … most often with a wickedly refreshing sense of humour which makes issues raised hit home all the harder. One of his starting points was a reaction to being questioned by college tutors, as to why an African artist should be interested in making work about Perestroika. This led to a whole chain of work questioning what people meant by African and European. He began with the idea of using fabric as a metaphor. Struck by the fact that batik cloth on sale in Brixton was actually manufactured in Holland, he realised that even the origins of the fabric speak of the inequities of global trade. This led the way to Double Dutch (1994) - a series of small paintings using motifs from batik cloth.

In an age when so many of us feel that buying Fairtrade coffee is doing our bit to rebalance global inequalities, much of Shonibare's work highlights the complexity and complicity which connects the materially advanced countries to the so-called third world. The richly patterned batik-based costumes adorning the headless figures in many of Shonibare's installations reference colonial exploitation, both past and present. Traditional motifs are interwoven with Gucci-style prints, in a way that is both entertaining and subversive. Describing his work as "soft politics", the beauty of the objects in themselves becomes part of the challenge to the status quo. Yinka Shonibare and Rachel Gadsden are among the surprisingly small group of disabled artists who have critically engaged with the issues of war in the contemporary world.

His work contains frequent references to English history. His art historical tableaux such as Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (after Gainsborough) and The Swing (after Fragonard), re-stage images of the aristocracy. Aside from taking a post-colonial swipe they ask questions about the current state of power relations in the world. Who are the anonymous heads behind big corporations who control so much of our lives and aspirations? Gallantry and Criminal Conversation (2002) and Scramble for Africa (2003) are more literal in their condemnation for the power relationships and global inequality forged by the ruling classes of Europe.

Inspired by A Rake's Progress by Hogarth, Shonibare's Diary of a Dandy consists of a series of photographic tableaux, putting himself in the frame. The work, which was on show on billboards on the London Underground during the early '90s, reflects the saccharine obsession for the costume drama, reflecting an idealised past. At the same time by placing himself as a Black, disabled, British man in the centre of the narrative, he questions the aspiration of wanting to achieve a position of power and affluence in contemporary society.

As he talked through his body of work, he talked occasionally but poignantly about his identity as a disabled man. Dorian Gray (2001) explores issues of disability and dandyism, beautifully illustrating Oscar Wilde's parable about the dangers of a society obsessed with the desire for perfection. Coming from a need to break out of the isolation of being alone in the studio, the work is also about the need to work in collaboration. More subtly it reflects a fear of being corrupted by a society steeped in hypocrisy, and the irony of having been launched as a foremost contemporary British artist by Charles Saatchi, engineer behind the Thatcher phenomenon.

The Adam Reynolds Bursary is unique in its aim to provide an opportunity for artists to develop their ideas and practice without pressure to deliver a particular outcome. The successful artist will be selected from an open submission, on the strength of their work and proposal.

http://www.disabilityartsonline.org.uk/yinka_shonibare_bursary

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Carlos Espartaco on Dandyism

Carlos Espartaco said about the American philosopher and poet Eduardo Sanguinetti:

"Only the dandy, last heir of the stoic tentative, has imposed himself in the world of appearance as a thing and has evaded fashion in the name of a "mode" that would be inseparable of him. Actually, it is necessary to summon the void in itself, to conqueror the cool way that qualifies the dandy, which is "thousand of kilometers farther from inmediate sensations". And for Eduardo Sanguinetti this means, in terms of the multiple strategics he will use in the passages from "anti-fashion" to "look" a radical self-empting that emancipates from time, but that does not reject the effort that has to do to register the emerging novelty. Obtaining this space resembles a landscape, where, in accordance with Baudelaire "carries Hercules upon his shoulders".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dandy

Albert Camus on Dandyism

Albert Camus said that:

The dandy creates his own unity by aesthetic means. But it is an aesthetic of negation. "To live and die before a mirror": that according to Baudelaire, was the dandy's slogan. It is indeed a coherent slogan. The dandy is, by occupation, always in opposition. He can only exist by defiance. Up to now, man derived his coherence from the Creator. But from the moment that he consecrates his rupture from Him, he finds himself delivered over to the fleeting moment, to the passing days, and to wasted sensibility. Therefore he must take himself in hand. The dandy rallies his forces and creates a unity for himself by the very violence of his refusal. Profligate, like all people without a rule of life, he is only coherent as an actor. But an actor implies a public; the dandy can only play a part by setting himself up in opposition. He can only be sure of his own existence by finding it in the expression of others' faces. Other people are his mirror. A mirror that quickly becomes clouded, it's true, since human capacity for attention is limited. It must be ceaselessly stimulated, spurred on by provocation. The dandy, therefore, is always compelled to astonish. Singularity is his vocation, excess his way to perfection. Perpetually incomplete, always on the fringe of things, he compels others to create him, while denying their values. He plays at life because he is unable to live it.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dandy

The Dandy

Dandy

Though previous manifestations of the petit-maître (Fr. for small master) and the Muscadin have been noted by John C. Prevost,[4] the modern practice of dandyism first appeared in the revolutionary 1790s, both in London and in Paris. The dandy cultivated skeptical reserve, yet to such extremes that the novelist George Meredith, himself no dandy, once defined "cynicism" as "intellectual dandyism"; nevertheless, the Scarlet Pimpernel is one of the great dandies of literature. Some took a more benign view; Thomas Carlyle in his book Sartor Resartus, wrote that a dandy was no more than "a clothes-wearing man". Honoré de Balzac introduced the perfectly worldly and unmoved Henri de Marsay in La fille aux yeux d'or (1835), a part of La Comédie Humaine, who fulfills at first the model of a perfect dandy, until an obsessive love-pursuit unravels him in passionate and murderous jealousy.

Charles Baudelaire, in the later, "metaphysical" phase of dandyism[5] defined the dandy as one who elevates æsthetics to a living religion,[6] that the dandy's mere existence reproaches the responsible citizen of the middle class: "Dandyism in certain respects comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" and "These beings have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking .... Contrary to what many thoughtless people seem to believe, dandyism is not even an excessive delight in clothes and material elegance. For the perfect dandy, these things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of his mind."

The linkage of clothing with political protest had become a particularly English characteristic during the 18th century.[7] Given these connotations, dandyism can be seen as a political protestation against the rise of levelling egalitarian principles, often including nostalgic adherence to feudal or pre-industrial values, such as the ideals of "the perfect gentleman" or "the autonomous aristocrat", though paradoxically, the dandy required an audience, as Susann Schmid observed in examining the "successfully marketed lives" of Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron, who exemplify the dandy's roles in the public sphere, both as writers and as personae providing sources of gossip and scandal.[8]

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

YINKA SHONIBARE MBE AND THE ART OF RESISTANCE Art Experience NYC

When the great lord passes the wise peasant bows deeply and silently farts’. Few weeks ago, while working in this review, I read this Ethiopian proverb, quoted by James Scott in his book Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990). Since then I have wondered how Yinka Shonibare MBE’s work could be related to this saying. In what follows I will try to answer this question.

In Domination and the Art of Resistance, scholar James Scott distinguishes between what he calls ‘public’ and ‘hidden’ transcripts. Imposed by the powerful, these public transcripts aim toward a self-celebration of the dominants, as well as the moral values and relations of production that allow the perpetuation of the status quo. They also have a theatrical character. Neither the ruling classes not their subjugated groups believe in them. Actually they both, in their respective ‘hidden transcripts’, usually see the other group with distrust and hostility. Nevertheless, the rituals of reverence and the adulation play a productive role in the relations of power. They allow the powerful to enact a sense of unity, presenting the oppressive regime as a timeless social order and rendering idealized images of the rulers. The oppressed, on the other hand, can take advantage of the public transcripts in order to introduce some subtle forms of opposition, like the wise peasant in the Ethiopian proverb does with his public reverence that contrasts with the silent act of disrespect.

YINKA SHONIBARE, MBE

Fake Death Picture (The Suicide – Manet), 2011

Digital chromogenic print

Framed: 58 1⁄2 x 71 1⁄4 in (148.59 x 180.98 cm)

©The Artist

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Fake Death Picture (The Suicide – Manet), 2011

Digital chromogenic print

Framed: 58 1⁄2 x 71 1⁄4 in (148.59 x 180.98 cm)

©The Artist

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Shonibare’s images could be seen as attempts to rewrite Eurocentric historical narratives by including black and mestizo characters attending to tragic scenes taken from Western painting—such as the death of Saint-Francis or Leonardo da Vinci—or playing a main role in a well-known Italian opera. In the series of pictures shown in his recent show at James Cohan Gallery, Addio del Passato (So Close My Sad Story) the main character—a dying white man—wears 18th century costumes made from fabrics that suggest a sense of “Africannness.” At first glance, these are vindications of the traditionally oppressed, post-colonized world, in its undermined place in global culture, history, politics and economics. However, Shonibare seems to go beyond these types of postcolonial parodies. He also points to identity issues in themselves. I would claim that in Shonibare’s work these issues related to national identities function as parodies of public transcripts that are reminiscent of a colonized past.

https://www.artexperiencenyc.com/yinka-shonibare-mbe-and-the-art-of-resistance/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)