- Introduction to Yinka Shonibare

- Yinka Shonibare Biography

- Yinka Shonibare CV

- England and Nigeria Today

- Batik- Dutch wax fabric

- Batik as a wax resist

- Heather Gatt

- Nigeria timeline

- Colonization of nigeria

- Resources of Nigeria

- Royal Niger Trading Co.

- Young British Artists

- Gillian Wearing

- Tracey Emin

- Aristocracy

- Aristocratic revolt in France

- Beheading and Marie Antoinette

- Lucid Decapitation

- Mike the Headless Chicken

- Yinka Shonibare ArtHistory.com Biography

- Interview with Anthony Downey for BOMB Magazine

- Synopsis of Swan Lake

- Yinka Shonibare and the Art of Resistance

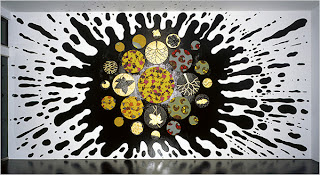

- Work by Yinka Shonibare

- The Dandy

- Albert Camus on Dandyism

- Carlos Esparataco on Dandysim

- Colin Hambrook and Joe McConnell repsond to Yinka Shonibare

- Disabled Artist- Stephan Wiltshire

- Disabled Artist- Alice Schonfield

- Disabled Artist- Matt Sesow

- Disabled Artist- Ping Lian Yeak

- Interview for crossing borders

- Reflective Summary

Monday, May 6, 2013

Table of Contents

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Reflective Summary

Yinka Shonibare is a remarkable artist who uses historical and modern ideas to create aesthetically interesting works of art. He creates tableaus that often reference historical works of art. He uses these classical allusions to add depth of meaning to his work. Yink Shonibare makes his work relevant to modern society by exploring the themes of colonization and aristocracy. These issues relate to the modern day situation of post-coloinzation Nigeria, as well as the vast separation of wealth in society. More recently, his work has become more performance based. I feel that this is a natural progression for his work. He started his practice by creating scenes to photograph, then moved to displaying the scenes. Now, Yinka Shonibare uses the scenes in motion in order to convey more information through his work.

Over the course of this research project, I explored the ideas of headlessness, Dandyism, Aristocracy, Nigerian history, YBA's. I also learned about batik fabric, and disabled artists. This exploration has expanded my knowledge significantly on Nigeria and England. This opportunity to explore new subjects will impact my in practice in positive ways. I have begun to use colors reminiscent of Yinka Shonibare's batik fabric. I am also seeing increased value in three dimensional work. After seeing the natural progression of Yinka Shonibare's work, I am contemplating the possibility of purifying my practice. Yinka Shonibare is able to remove distractions and unnecessary components of his work by showing the essence of what he is trying to say.

Over the course of this research project, I explored the ideas of headlessness, Dandyism, Aristocracy, Nigerian history, YBA's. I also learned about batik fabric, and disabled artists. This exploration has expanded my knowledge significantly on Nigeria and England. This opportunity to explore new subjects will impact my in practice in positive ways. I have begun to use colors reminiscent of Yinka Shonibare's batik fabric. I am also seeing increased value in three dimensional work. After seeing the natural progression of Yinka Shonibare's work, I am contemplating the possibility of purifying my practice. Yinka Shonibare is able to remove distractions and unnecessary components of his work by showing the essence of what he is trying to say.

Interview for crossing borders

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/crossingborders/interview/yinka_interview.html

In this interview Yinka Shonibare explains how his Nigerian and English bi-cultural background has informed his practice. He discusses the key themes he explores including global issues and the question of identity in today's world. He explains in detail the ideas conveyed though his sculpture, The Reverend on ice, 2005 and his film Un ballo in maschero, 2004. The artist's fascination for costume, patterned fabrics, art history and the concept of the dandy are also discussed in relation to his work.

In this interview Yinka Shonibare explains how his Nigerian and English bi-cultural background has informed his practice. He discusses the key themes he explores including global issues and the question of identity in today's world. He explains in detail the ideas conveyed though his sculpture, The Reverend on ice, 2005 and his film Un ballo in maschero, 2004. The artist's fascination for costume, patterned fabrics, art history and the concept of the dandy are also discussed in relation to his work.

Saturday, May 4, 2013

Disabled Artist- Ping Lian Yeak

Ping Lian Yeak

Disability: Autistic SavantPing Lian is an autistic savant who has been producing amazing art since his childhood. He is now fifteen. More of his amazing art may be viewed at his website.

http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2010/03/the-amazing-art-of-disabled-artists/

Disabled Artist- Matt Sesow

Matt Sesow

Disability: Missing a handJust six years after losing his hand as a child in an accident in which a crashed plane severed his arm and took away his dominant hand, Sesow played for the US team in the disabled Olympics in England. While working at IBM as a software engineer, he began painting scenes in oils that were influenced by his traumatic injury.

http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2010/03/the-amazing-art-of-disabled-artists/

Disabled Artist- Alice Schonfield

Alice Schonfield

Disability: Diminished capacity through multiple strokesAlthough Alice Schonfeld is most known for her sculpting work primarily in Italian marble, she is also regarded as an inspirational figure for the disabled community. She has shown a considerable tenacity to work through debilitating illnesses and has done a lot to promote awareness of disable artists. She resides in California.

Disabled artist- Stephan Wiltshire

Stephen Wiltshire

Disability: Autistic SavantWiltshire was born in 1974 in London to West Indian parents. He is an autistic savant and world famous architectural artist. He learned to speak at the age of nine, and at the age of ten began drawing detailed sketches of London landmarks. While he has created many prodigious works of art, his most recent was a eighteen foot wide panoramic landscape of the skyline of New York City, after only viewing it once during a twenty minute helicopter ride.

Colin Hambrook and Joe McConnell respond to a talk by Yinka Shonibare at Shape's launch of the Adam Reynolds bursary

The Adam Reynolds Memorial Bursary was launched at the Camden Arts Centre in

July 2007. The bursary offers disabled or Deaf visual artists a £5,000

award and a year-long artistic residency. In the first year, this will

be hosted by Camden Arts Centre, where Adam himself had a residency at a

pivotal time in his career. The bursary is in memory of Adam Reynolds,

who died in 2005. Adam was a Chairman on Shape's Board of Trustees, a

renowned sculptor and an activist for disability equality in the arts.

Yinka Shonibare opened the event with a few of his own memories of Adam from the time when Shonibare worked as an Arts Officer for Shape. He talked with affection of Adam's supportiveness and eloquence, and in particular his passion for artist-run projects, such as the Adam Gallery, which he set up in 1984. It was unique in that it made the brave move to bypass curatorial and commercial precedents and to put the creative process firmly in the hands of the artist. These ideas rubbed off on Shonibare, setting him on the road to increasingly complex and involved collaborations through a range of media that includes sculpture, painting, photography, film and installation.

Although not a member of the Disability Arts movement, Shonibare readily acknowledges physical disability as part of his identity but creates work in which this is just one strand of a far richer weave. “Historically the people who made huge, unbroken modernist paintings were middle-class white American men. I don't have that physique; I can't make that work. So I fragmented it, in a way which made it both physically manageable and emphasizes the political critique”.(Conversation with Nancy Hynes cited in www.findarticles.com).

Shonibare's prolific work embraces a wide range of themes: identity, history, global politics … most often with a wickedly refreshing sense of humour which makes issues raised hit home all the harder. One of his starting points was a reaction to being questioned by college tutors, as to why an African artist should be interested in making work about Perestroika. This led to a whole chain of work questioning what people meant by African and European. He began with the idea of using fabric as a metaphor. Struck by the fact that batik cloth on sale in Brixton was actually manufactured in Holland, he realised that even the origins of the fabric speak of the inequities of global trade. This led the way to Double Dutch (1994) - a series of small paintings using motifs from batik cloth.

In an age when so many of us feel that buying Fairtrade coffee is doing our bit to rebalance global inequalities, much of Shonibare's work highlights the complexity and complicity which connects the materially advanced countries to the so-called third world. The richly patterned batik-based costumes adorning the headless figures in many of Shonibare's installations reference colonial exploitation, both past and present. Traditional motifs are interwoven with Gucci-style prints, in a way that is both entertaining and subversive. Describing his work as "soft politics", the beauty of the objects in themselves becomes part of the challenge to the status quo. Yinka Shonibare and Rachel Gadsden are among the surprisingly small group of disabled artists who have critically engaged with the issues of war in the contemporary world.

His work contains frequent references to English history. His art historical tableaux such as Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (after Gainsborough) and The Swing (after Fragonard), re-stage images of the aristocracy. Aside from taking a post-colonial swipe they ask questions about the current state of power relations in the world. Who are the anonymous heads behind big corporations who control so much of our lives and aspirations? Gallantry and Criminal Conversation (2002) and Scramble for Africa (2003) are more literal in their condemnation for the power relationships and global inequality forged by the ruling classes of Europe.

Inspired by A Rake's Progress by Hogarth, Shonibare's Diary of a Dandy consists of a series of photographic tableaux, putting himself in the frame. The work, which was on show on billboards on the London Underground during the early '90s, reflects the saccharine obsession for the costume drama, reflecting an idealised past. At the same time by placing himself as a Black, disabled, British man in the centre of the narrative, he questions the aspiration of wanting to achieve a position of power and affluence in contemporary society.

As he talked through his body of work, he talked occasionally but poignantly about his identity as a disabled man. Dorian Gray (2001) explores issues of disability and dandyism, beautifully illustrating Oscar Wilde's parable about the dangers of a society obsessed with the desire for perfection. Coming from a need to break out of the isolation of being alone in the studio, the work is also about the need to work in collaboration. More subtly it reflects a fear of being corrupted by a society steeped in hypocrisy, and the irony of having been launched as a foremost contemporary British artist by Charles Saatchi, engineer behind the Thatcher phenomenon.

The Adam Reynolds Bursary is unique in its aim to provide an opportunity for artists to develop their ideas and practice without pressure to deliver a particular outcome. The successful artist will be selected from an open submission, on the strength of their work and proposal.

Yinka Shonibare opened the event with a few of his own memories of Adam from the time when Shonibare worked as an Arts Officer for Shape. He talked with affection of Adam's supportiveness and eloquence, and in particular his passion for artist-run projects, such as the Adam Gallery, which he set up in 1984. It was unique in that it made the brave move to bypass curatorial and commercial precedents and to put the creative process firmly in the hands of the artist. These ideas rubbed off on Shonibare, setting him on the road to increasingly complex and involved collaborations through a range of media that includes sculpture, painting, photography, film and installation.

Although not a member of the Disability Arts movement, Shonibare readily acknowledges physical disability as part of his identity but creates work in which this is just one strand of a far richer weave. “Historically the people who made huge, unbroken modernist paintings were middle-class white American men. I don't have that physique; I can't make that work. So I fragmented it, in a way which made it both physically manageable and emphasizes the political critique”.(Conversation with Nancy Hynes cited in www.findarticles.com).

Shonibare's prolific work embraces a wide range of themes: identity, history, global politics … most often with a wickedly refreshing sense of humour which makes issues raised hit home all the harder. One of his starting points was a reaction to being questioned by college tutors, as to why an African artist should be interested in making work about Perestroika. This led to a whole chain of work questioning what people meant by African and European. He began with the idea of using fabric as a metaphor. Struck by the fact that batik cloth on sale in Brixton was actually manufactured in Holland, he realised that even the origins of the fabric speak of the inequities of global trade. This led the way to Double Dutch (1994) - a series of small paintings using motifs from batik cloth.

In an age when so many of us feel that buying Fairtrade coffee is doing our bit to rebalance global inequalities, much of Shonibare's work highlights the complexity and complicity which connects the materially advanced countries to the so-called third world. The richly patterned batik-based costumes adorning the headless figures in many of Shonibare's installations reference colonial exploitation, both past and present. Traditional motifs are interwoven with Gucci-style prints, in a way that is both entertaining and subversive. Describing his work as "soft politics", the beauty of the objects in themselves becomes part of the challenge to the status quo. Yinka Shonibare and Rachel Gadsden are among the surprisingly small group of disabled artists who have critically engaged with the issues of war in the contemporary world.

His work contains frequent references to English history. His art historical tableaux such as Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (after Gainsborough) and The Swing (after Fragonard), re-stage images of the aristocracy. Aside from taking a post-colonial swipe they ask questions about the current state of power relations in the world. Who are the anonymous heads behind big corporations who control so much of our lives and aspirations? Gallantry and Criminal Conversation (2002) and Scramble for Africa (2003) are more literal in their condemnation for the power relationships and global inequality forged by the ruling classes of Europe.

Inspired by A Rake's Progress by Hogarth, Shonibare's Diary of a Dandy consists of a series of photographic tableaux, putting himself in the frame. The work, which was on show on billboards on the London Underground during the early '90s, reflects the saccharine obsession for the costume drama, reflecting an idealised past. At the same time by placing himself as a Black, disabled, British man in the centre of the narrative, he questions the aspiration of wanting to achieve a position of power and affluence in contemporary society.

As he talked through his body of work, he talked occasionally but poignantly about his identity as a disabled man. Dorian Gray (2001) explores issues of disability and dandyism, beautifully illustrating Oscar Wilde's parable about the dangers of a society obsessed with the desire for perfection. Coming from a need to break out of the isolation of being alone in the studio, the work is also about the need to work in collaboration. More subtly it reflects a fear of being corrupted by a society steeped in hypocrisy, and the irony of having been launched as a foremost contemporary British artist by Charles Saatchi, engineer behind the Thatcher phenomenon.

The Adam Reynolds Bursary is unique in its aim to provide an opportunity for artists to develop their ideas and practice without pressure to deliver a particular outcome. The successful artist will be selected from an open submission, on the strength of their work and proposal.

http://www.disabilityartsonline.org.uk/yinka_shonibare_bursary

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Carlos Espartaco on Dandyism

Carlos Espartaco said about the American philosopher and poet Eduardo Sanguinetti:

"Only the dandy, last heir of the stoic tentative, has imposed himself in the world of appearance as a thing and has evaded fashion in the name of a "mode" that would be inseparable of him. Actually, it is necessary to summon the void in itself, to conqueror the cool way that qualifies the dandy, which is "thousand of kilometers farther from inmediate sensations". And for Eduardo Sanguinetti this means, in terms of the multiple strategics he will use in the passages from "anti-fashion" to "look" a radical self-empting that emancipates from time, but that does not reject the effort that has to do to register the emerging novelty. Obtaining this space resembles a landscape, where, in accordance with Baudelaire "carries Hercules upon his shoulders".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dandy

Albert Camus on Dandyism

Albert Camus said that:

The dandy creates his own unity by aesthetic means. But it is an aesthetic of negation. "To live and die before a mirror": that according to Baudelaire, was the dandy's slogan. It is indeed a coherent slogan. The dandy is, by occupation, always in opposition. He can only exist by defiance. Up to now, man derived his coherence from the Creator. But from the moment that he consecrates his rupture from Him, he finds himself delivered over to the fleeting moment, to the passing days, and to wasted sensibility. Therefore he must take himself in hand. The dandy rallies his forces and creates a unity for himself by the very violence of his refusal. Profligate, like all people without a rule of life, he is only coherent as an actor. But an actor implies a public; the dandy can only play a part by setting himself up in opposition. He can only be sure of his own existence by finding it in the expression of others' faces. Other people are his mirror. A mirror that quickly becomes clouded, it's true, since human capacity for attention is limited. It must be ceaselessly stimulated, spurred on by provocation. The dandy, therefore, is always compelled to astonish. Singularity is his vocation, excess his way to perfection. Perpetually incomplete, always on the fringe of things, he compels others to create him, while denying their values. He plays at life because he is unable to live it.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dandy

The Dandy

Dandy

Though previous manifestations of the petit-maître (Fr. for small master) and the Muscadin have been noted by John C. Prevost,[4] the modern practice of dandyism first appeared in the revolutionary 1790s, both in London and in Paris. The dandy cultivated skeptical reserve, yet to such extremes that the novelist George Meredith, himself no dandy, once defined "cynicism" as "intellectual dandyism"; nevertheless, the Scarlet Pimpernel is one of the great dandies of literature. Some took a more benign view; Thomas Carlyle in his book Sartor Resartus, wrote that a dandy was no more than "a clothes-wearing man". Honoré de Balzac introduced the perfectly worldly and unmoved Henri de Marsay in La fille aux yeux d'or (1835), a part of La Comédie Humaine, who fulfills at first the model of a perfect dandy, until an obsessive love-pursuit unravels him in passionate and murderous jealousy.

Charles Baudelaire, in the later, "metaphysical" phase of dandyism[5] defined the dandy as one who elevates æsthetics to a living religion,[6] that the dandy's mere existence reproaches the responsible citizen of the middle class: "Dandyism in certain respects comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" and "These beings have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking .... Contrary to what many thoughtless people seem to believe, dandyism is not even an excessive delight in clothes and material elegance. For the perfect dandy, these things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of his mind."

The linkage of clothing with political protest had become a particularly English characteristic during the 18th century.[7] Given these connotations, dandyism can be seen as a political protestation against the rise of levelling egalitarian principles, often including nostalgic adherence to feudal or pre-industrial values, such as the ideals of "the perfect gentleman" or "the autonomous aristocrat", though paradoxically, the dandy required an audience, as Susann Schmid observed in examining the "successfully marketed lives" of Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron, who exemplify the dandy's roles in the public sphere, both as writers and as personae providing sources of gossip and scandal.[8]

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

YINKA SHONIBARE MBE AND THE ART OF RESISTANCE Art Experience NYC

When the great lord passes the wise peasant bows deeply and silently farts’. Few weeks ago, while working in this review, I read this Ethiopian proverb, quoted by James Scott in his book Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990). Since then I have wondered how Yinka Shonibare MBE’s work could be related to this saying. In what follows I will try to answer this question.

In Domination and the Art of Resistance, scholar James Scott distinguishes between what he calls ‘public’ and ‘hidden’ transcripts. Imposed by the powerful, these public transcripts aim toward a self-celebration of the dominants, as well as the moral values and relations of production that allow the perpetuation of the status quo. They also have a theatrical character. Neither the ruling classes not their subjugated groups believe in them. Actually they both, in their respective ‘hidden transcripts’, usually see the other group with distrust and hostility. Nevertheless, the rituals of reverence and the adulation play a productive role in the relations of power. They allow the powerful to enact a sense of unity, presenting the oppressive regime as a timeless social order and rendering idealized images of the rulers. The oppressed, on the other hand, can take advantage of the public transcripts in order to introduce some subtle forms of opposition, like the wise peasant in the Ethiopian proverb does with his public reverence that contrasts with the silent act of disrespect.

YINKA SHONIBARE, MBE

Fake Death Picture (The Suicide – Manet), 2011

Digital chromogenic print

Framed: 58 1⁄2 x 71 1⁄4 in (148.59 x 180.98 cm)

©The Artist

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Fake Death Picture (The Suicide – Manet), 2011

Digital chromogenic print

Framed: 58 1⁄2 x 71 1⁄4 in (148.59 x 180.98 cm)

©The Artist

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Shonibare’s images could be seen as attempts to rewrite Eurocentric historical narratives by including black and mestizo characters attending to tragic scenes taken from Western painting—such as the death of Saint-Francis or Leonardo da Vinci—or playing a main role in a well-known Italian opera. In the series of pictures shown in his recent show at James Cohan Gallery, Addio del Passato (So Close My Sad Story) the main character—a dying white man—wears 18th century costumes made from fabrics that suggest a sense of “Africannness.” At first glance, these are vindications of the traditionally oppressed, post-colonized world, in its undermined place in global culture, history, politics and economics. However, Shonibare seems to go beyond these types of postcolonial parodies. He also points to identity issues in themselves. I would claim that in Shonibare’s work these issues related to national identities function as parodies of public transcripts that are reminiscent of a colonized past.

https://www.artexperiencenyc.com/yinka-shonibare-mbe-and-the-art-of-resistance/

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Synopsis of Swan Lake

Swan Lake

The story of Swan Lake is woven around two girls, Odette and Odile, who resemble each other so closely they can easily be mistaken for the other. Originally their roles were entrusted to two separate dancers, but as there is only one brief fleeting moment when they are seen simultaneously, it has long been customary for a single prima ballerina to perform both parts, differentiating them by characterisation and general style. The action takes place in Germany in the distant past.

Act I

After a glittering musical introduction, the first scene is set in a splendid park, with a fairy-tale castle in the background. Prince Seigfried and his friends are seated, drinking, and peasants enter to congratulate him on his coming of age; meanwhile, his tutor Wolfgang encourages them to dance for the young Prince's entertainment.

A messanger presages the arrival of the young Prince's Mother. She follows to pronounce that her son should now marry, choosing a bride from the young women to be presented to him at a ball the following evening. She leaves and the rustic dancing resumes until darkness suddenly falls and a flock of swans appear. The Prince has an idea of shooting one of the noble birds and, armed with a crossbow, sets off with his friends and heads to where the swans are heading.

Act II

By the banks of a lake by moonlight, a flight of swans glide past, led by their own Queen. The Prince's friends are eager for the chase, but he begs them to leave him, and whilst he is alone the Swan Queen comes to him in the human form of Odette and tells her story.

She is under the spell of an evil magician, Von Rothbart, and reveals that by day she and her friends are turned into swans. Also persecuted by her stepmother, that subjection will only end when she marries; until then she has only her crown to protect her.

The whole swan group arrives and they reproach the Prince for attempting to deprive them of their beloved leader. Odette intercedes and the Prince discards his crossbow. He and Odette dance, professing their love. The entire flock joins in; and the act ends as an owl (the wicked stepmother) flaps heavily above.

Act III

It is the following evening and in a luxurious hall in the Prince's castle preparations are underway for the feast. Wolfgang orders the servants around; guests start to materialise; and finally, the Princess-Mother and her entourage. A sequence of turns commences until the Princess asks her son which of the women he favours. 'None', he replies to her annoyance.

At a sudden fanfare Baron Rothbart enters with his daughter Odile, whose resemblance to Odette strikes the Prince. Odile herself dances enticingly, followed by an elaborate sequence of national dances by the company. The Princess-Mother is pleased to see that Odile has caught her son's favour. The young couple themselves conjoin together and the Princess-Mother and Rothbart advance to centre-stage to announce a betrothal.

With that, the scene ominously darkens, an agitated version of the principal swan theme is heard; a window flies open noisily and through it can be seen a white swan replete with crown. Horrified, the Prince pushes Odile away and rushes out amid general confusion.

Act IV

The girls, including Odette, gather around the lake. Odette is heartbroken. Prince Siegfried finds them consoling each other. He explains to Odette the trickery of Von Rothbart and she grants him her forgiveness. It isn’t long before Von Rothbart appears and tells the prince that he must honour his word and marry his daughter or both he and Odette will die. Prince Siegfried refuses. A fight follows, Odette and Siegfried die in each other’s arms. Von Rothbart’s evil spell is broken by the power of Odette and Siegfried’s love for each other and Von Rothbart is destroyed by the swans, who are released from their enslavement..

Interview with Anthony Downey for BOMB magazine

Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball), 2004, color digital video, 32-minute loop. Images courtesy of the artist, James Cohan Gallery, New York, and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

Yinka Shonibare first came to widespread attention through his use of Dutch wax fabric, which he has used both as the ground of his paintings and to clothe his sculptures. This bright and distinctive fabric was originally produced in Dutch Indonesia, where no market was found for it, and subsequently copied and produced by the English, who eventually sold it to West Africans, for whom it became a popular everyday item of clothing. It also, crucially, became a sign of identitarian “authenticity” both in Africa and, later, for Africans in England. A colonial invention, Dutch wax fabric offers itself as both a fake and yet “authentic” sign of Africanness, and Shonibare’s use of it in his paintings and sculptures accentuates a politics of (in)authenticity by simultaneously presenting both the ideal of an “authentic” identity and identity as a “fabrication.” Although he has been producing mostly installation-based work of late, Shonibare is also an accomplished painter, and that is where his practice began in the ’80s. It is also easy to overlook, in all the theorizing about postcoloniality and the politics of identity, the amount of amusement and frivolity he can pack into his work.

Shonibare was recently nominated for the Turner Prize and used the opportunity to screen his first film, Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball), 2004. Taking as its starting point the controversial figure of King Gustav III of Sweden, who was assassinated in 1792, Shonibare weaves an intricate and enigmatic tale. Employing the medium of dance, the film explores a number of conceptual and choreographical ambiguities, not least the indeterminacies of identity and gender implicit in the use of costumes and masks. On a formal level Shonibare’s use of repetition and the lack of dialogue forgo the conventions of mainstream film and those associated with so-called realist narrative. The events represented in the film, despite their apparent historical remoteness, also resonate within contemporary political debates on the nature of power and the excess associated with authoritarian regimes.

Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball), 2004, color digital video, 32-minute loop.

Anthony Downey Let’s start with Un Ballo in Maschera. Why this turn to film?

Yinka Shonibare My work has always used a theatrical language. The first time I did anything filmic was in photography: The Picture of Dorian Gray [2001] was actually a series of stills from a film in which I acted out the various parts in Dorian Gray. I’ve always wanted to do film, but I did photography, I did stills, because I just did not have the resources to make the kind of film I envisioned. My work comments on power, or the deconstruction of power, and I tend to use notions of excess as a way to represent that power—deconstructing things within that. I needed to do something very elaborate in this case, and of course that would require financial resources. The production of Un Ballo in Maschera was a collaboration between Moderna Museet in Stockholm and Swedish television. The agreement with Swedish television was that they would make a documentary of me making the film, and that was what they would show, but when they saw the finished film they created prime-time space for it. I thought that was very impressive, to have an art film on the Swedish equivalent of the BBC at 8:00 PM. Then again, the interest in art in Stockholm and Sweden generally, the interest in culture, is quite high. But back to your question: I’d also wanted to link my costume work with the masquerade performance aspect of my practice, and it seems a progressive logic to move from the photographic work and the tableaus with the paintings I’d done and conclude with film.

AD I would like to further link the notion of excess with the idea of theatricality in your work. Do you see that excess as something beyond theater?

YS The main preoccupation within my art education was the construction of signs as outlined in Roland Barthes’s Mythologies. So the idea of the theatrical for me is actually about art as the construction of a fiction, art as the biggest lie. What I want to suggest is that there is no such thing as a natural signifier, that the signifier is always constructed—in other words, that what you represent things with is a form of mythology. Representation itself comes into question. I think that theater enables you to really emphasize that fiction. For example, in The Picture of Dorian Gray, a black man plays within an upper-class 19th-century setting, and also in The Diary of a Victorian Dandy. The theatrical is actually a way of re-presenting the sign.

AD What you’re saying is that the sign itself is unstable, which ties into the notion of the identitarian ambiguity that you bring out in the masquerade in Un Ballo in Maschera.

YS It goes further than that. On the one hand, the masquerade is about ambiguity, but on the other hand—and you could take the masquerade festivals in Venice and Brazil as examples—it involves a moment when the working classes could play at being members of the aristocracy for a day, and vice versa. We’re talking about power within society, relations of power. As a black person in this context, I can create fantasies of empowerment in relation to white society, even if historically that equilibrium or equality really hasn’t arrived yet. It’s like the carnival itself, where a working-class person can occupy the position of master for however long the Venice carnival goes on—and it goes on for ages—and members of the aristocracy could take on the role of the working class and get as wild and as drunk as possible. So the carnival in this sense is a metaphor for the way that transformation can take place. This is something that art is able to do quite well, because it’s a space of transformation, where you can go beyond the ordinary.

Big Boy, 2002, wax printed cotton fabric and fiberglass, dimensions variable.

AD That’s quite a nice phrase—”fantasies of empowerment”—very Fanon-esque. I’m interested in this notion of carnivalesque masquerade, the way it inverts power relations. Do you see the political itself as a masquerade?

YS Well, Un Ballo in Maschera, believe it or not, was inspired by the current global situation, particularly the war in Iraq. I was thinking about King Gustav III of Sweden, who was fighting many wars on many fronts—with Russia, with Denmark—and spending a lot of money; as a result of this high spending, his population was impoverished, suffering. He was also an actor and a dandy, and he started the art academies in Sweden. He modeled himself on the French court and only spoke French. But he was fiddling while Rome was burning. There was a conspiracy to kill him. He loved masked balls, and he loved the theater, and it was while he was at one of those balls that he was assassinated. So I used him as a metaphor for power and its deconstruction. But there is an opportunity within my film for redemption. Things that happen get undone: the king gets killed, but he gets up again, and at the end of the film he steps backward, out of the scene. And, of course, I also played with gender positions, changing them around. The “power” in my film is a woman, and the assassin is also a woman dressed as a man.

Structurally, I didn’t want a narrative that was beginning, middle, end; I wanted to look formally at the way film is presented. In the museum setting, films are usually played in a loop. What I decided to do with this film was to ask all the actors to act the idea of the loop. What you see when the action comes around again is actually a reenactment of what went before; it’s not an electronic loop, it’s imitating one. I wanted the audience to participate, to try to work it out: Okay, the second time around, that actor was not quite where he was before. It was a way of looking at formal repetition and also the way history repeats. From the Roman to the Ottoman Empire, we have this repetition of power that always returns to the same point—the ambition to expand imperially is not very different from what’s going on now. As an artist, I won’t take a moral position; I think it’s important not to work for any one side politically. You need to keep your objectivity, unless you’re in Stalinist Russia. But what you can do is place a number of options in front of people so that they can think through them.

AD The act of not taking sides would seem to be part of an ethical, rather than political, approach if we’re looking at Un Ballo in Maschera as a historical metaphor for political redemption. Is the film a direct comment on the present day in this sense?

YS I give the audience two options. You see the king go into the ball, indulge himself in the excess and get murdered. But I give him the option to get up again. It’s up to the audience to decide which version prevails. Do they want him to stay murdered, or do they want him to be saved? The audience is seeing both possibilities. In real life, of course, there is no rewind, or replay; an event happens and that’s it.

AD So you’re asking the audience to be complicit, if not in the assassination, then in the redemption.

YS It depends on the person. Viewers have to make up their mind whether this person had the right to assassinate that leader or not. You need a leader, but what sort of leader? The film gives you the opportunity to engage with the various tensions. In the dance and the theatricality as well as the breathtaking visuals, you’re part of that excess and you indulge in it, but then it’s not that simple because there’s a dark side to this beauty. It’s not just a lavish banquet; there’s always this “terrible beauty.”

AD “All changed, changed utterly. A terrible beauty is born.” It’s a particularly apposite quote from W. B. Yeats, bearing in mind that it comes from a poem that expresses his own disillusionment with revolution.

YS Yes, so there’s always this thing that isn’t what you imagined it to be at first.

AD There’s also an absence of dialogue in your film. That was obviously intentional in the presentation of visual rather than aural excess. Is this what Barthes calls jouissance, the literal pleasure in the image itself?

YS It’s really about the presence of the actors. I wanted to avoid linear narrative, and dialogue sometimes makes that difficult unless I were to use dialogue in a very sophisticated manner. I didn’t want to distract from the presence of the actors. I left in things that would be taken out in “normal” film, like the effort of their dancing, or their breathing, or the sound of their clothes. Everything’s exaggerated so that you can just focus on the people, on the movement, on the visuals. That also gave the action a slightly disturbing quality, which I liked.

Scramble for Africa, 2003, 14 figures, 14 chairs and table, mixed media, 52×192 x 110”.

AD I quite like the idea of redemption as an ethical or relative, rather than political, gesture.

YS I don’t force that notion onto the audience. You have the opportunity to rethink these things, but you don’t necessarily have to. There are people who believe that the war in Iraq is absolutely right, as there are people who believe that it is absolutely wrong. There are two sides, and I think that’s what an artist has to recognize: positions are always relative.

AD And not taking a side is in fact taking a side, insofar as it opens a third space, beyond that easy agreement or disagreement.

YS Even racism is about relativity, do you see what I mean? I guess as an artist that relativity is what I want to highlight and play with. According to Brecht, the audience completes the work of art, and that is a notion I very much subscribe to.

AD Also the Brechtian idea that you have to draw attention to the artifice of the theater in order to involve yourself politically in what is happening.

I know you’re a big film buff. I want to talk about the importance of film for you. I mean particular filmmakers, particular films. I know you’ve cited Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover as a film that interests you.

YS Actually, for Un Ballo in Maschera I looked to that film again, because it shows how ridiculous excess can be, and how when you push it further, it becomes extremely primitive: the primitive side of humanity. I also like the pace of the film, the darkness of it, and its form. There are also some Godard films in which he focuses on form. You can do that with art; you can reference your form quite easily in a way that people understand. But with the saturation of Hollywood cinema there has also been a return to the idea of referencing the form of the film itself, which the great modernist filmmakers, particularly the French, were doing. This was something I felt I wanted to do: make an art film that refers to itself.

AD Two things come to mind: the long shot in Godard’s Weekend that tracks along a road of burning cars, and the circular narrative of Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad.

YS Yes, Resnais used the device of repetition in that film. That’s a very good one to reference, because of the sheer excess of that film: they’re all in this amazing hotel. It’s certainly one of my favorite films. French New Wave cinema is probably my favorite period of film. You can watch them over and over again and see something new every time.

AD It’s a formal device. They don’t introduce repetition as mere repetition, but repetition as difference, so to speak, because you’re looking again and again. For example, I was looking atUn Ballo in Maschera again to see what’s different from when I watched it before. It’s a re-thinking as well as a re-looking. In a way it’s repetition as the introduction of ambiguity and camouflage. Which brings me to the notion of ambiguity in your work, not least in your use of Dutch wax fabric. That fabric is a classic example of the so-called signifier of African authenticity, and yet it was produced by the Dutch for sale in Indonesia and then ended up in Nigeria. There is this notion of fabrication in your work—fabric itself, of course, but also fabrication, the telling of stories.

YS To be an artist, you have to be a good liar. There’s no question about that. If you’re not, you can’t be a good artist. Basically, you have to know how to fabricate, how to weave tales, how to tell lies, because you’re taking your audience to a nonexistent space and telling them that it does exist. But you have to be utopian in your approach. You have to create visions that don’t actually exist yet in the world—or that may actually someday exist as a result of life following art. It’s natural for people to want to be sectarian or divisive. Different cultures want to group together, they want to stick to their own culture, but what I do is create a kind of mongrel. In reality most people’s cultures have evolved out of this mongrelization, but people don’t acknowledge that. British culture in reality is very mixed. There’s a way in which people want to keep this notion of purity, and that ultimately leads to the gas chambers. What I am doing may be humorous so as to show the stupidity of things. But at the same time I understand that the logical conclusion of sectarianism is Auschwitz, or the “logical” in its starkest manifestation. So even though these works are humorous, there’s a very dark underlying motivation.

Odile and Odette, 2005, color film.

AD Which puts you in a position of playing out the carnivalesque yourself, because essentially it is carnivalesque to engage humorously with a very serious subject. This is precisely what Mikhail Bakhtin talks about when he explores the notion of the carnivalesque, the humorous taking down, or usurpation, of power. How do you feel about your own power relation to the audience, or your power to produce the work? Are those issues for you personally?

YS It’s very interesting: even though I make work about power, the so-called establishment and so on, I was made a Member of the British Empire. I am now Yinka Shonibare MBE, and of course there was the question of whether I was going to refuse the honor. The poet Benjamin Zephaniah, who is of Caribbean origin, had refused—I think it was an OBE. In the end, I felt that, given what my work is about, to have actually been acknowledged and honored by the establishment was quite interesting. And I felt it was more useful to accept it than to refuse it. Maybe I’m a bit old-fashioned, but I think it’s better to make an impact from within rather than from without. In a way I feel flattered, because I never really thought the establishment took any notice of what artists did.

AD Unless you’re advocating armed revolution.

YS Yes. So it’s quite amusing for me. And hopefully it’s a platform that will enable me to do more work.

AD In order to deconstruct those power structures, you must be engaged with them. I mean, standing outside throwing the proverbial Molotov cocktail is only going to get you so far. However, once you are inside—hidden, or cloaked‚ within those structures—there is a totally different power structure to be addressed. Which again brings in the carnivalesque, masquerade and the notion of camouflage.

YS Well, it’s the notion of the Trojan horse. With the Trojan horse, you can go in unnoticed. And then you can wreak havoc.

AD I like this notion of appearing as something you’re not, or making the work look like something it isn’t. People might look at your work and think of it in terms of decoration, but it is not that. You use decoration as a sign of excess.

YS And it is actually also decoration, because it is a deliberate complicity with popular culture. I once heard Howard Hodgkin say that he was offended because his work had been described as decorative. I don’t feel that way, because I deliberately use popular culture. A very interesting thing has now happened in the London fashion world since my Turner Prize nomination: a number of designers have taken on my work by using “African” textiles in a big way. It’s showing up in a lot of collections. If you go to the High Street fashion stores in London, you’ll see clothes, dresses, bags and things made out of those fabrics. It’s kind of exploded. In fact, Harvey Nichols invited me to do their window dressing. I turned it down. I was not totally opposed to it in principle; I was just too busy. But the good thing about that is that they went ahead and did a kind of Yinka Shonibare window anyway. So I like that sort of relationship between popular culture and art, the kind of to-ing and fro-ing. Do you see what I mean?

AD Absolutely. It creates a sort of fluidity and a certain ambiguity. You are not quite sure what the difference is—if indeed there is one—between the fabrics encountered in the “downmarket” environment of Brixton market or the so-called upmarket environment of Harvey Nichols.

YS And also the moment this fabric gets shown at the Turner Prize exhibition, at the Tate, suddenly it becomes chic. It’s the way the so-called outsider stuff—”peasant” clothes, for example—suddenly became chic.

AD Which is a good metaphor for masquerade and the carnivalesque: when the low becomes high and the high becomes low.

YS It’s interesting that the very wealthy go to Harvey Nichols and buy a very expensive fashion of something, when they could just go to Brixton market, buy the fabric and have it made very cheaply.

Odile and Odette, 2005, color film.

AD Let’s move on to your latest project, which is something else entirely. You’ve been working with the Royal Opera House on your version of Swan Lake, which you are callingOdile and Odette. Can you talk about how that came about, and then perhaps about what that project is and how it fits in—if indeed it does—with the discussion we’ve had?

YS Throughout 2005 there has been a celebration of African culture in London, called “Africa ’05,” for which a number of institutions around the city are doing projects relating to African culture. The Africa Centre approached me to do an installation there. The Africa Centre is at Covent Garden, and that’s also where the Royal Opera House is, so because of the proximity of the two, I proposed a project with the Royal Opera House. I thought that would be a great opportunity to look at the relationship between the Royal Opera House and the Africa Centre, both institutions representing a colonial relationship and a cultural relationship. The Africa Centre exists as a result of England’s encounter with Africa. But then I thought, What would I do at the Royal Opera House? I tried to go beyond what would be expected of somebody of African origin and I thought, I’ve never done a ballet, so why not? You laugh, but you know, no one ever questioned Picasso’s interest in and use of African art, but Africans are always expected to just do “African” things. In the contemporary world where we all travel, that’s just not realistic. I see opera like everybody else, and I see popular culture like everybody else. I always like to work with iconic things, and Swan Lake is very well known, probably the most popular ballet. It’s also a perfect choice because the basic story concerns a prince who wants to get married, and there’s a good, sweet swan, Odette, and a bad swan, Odile. Usually the two roles are danced by the same ballerina. In all productions Odile is put into black clothes and Odette wears swanlike, nicer things. The roles—one as the ego and one as alter—in my version are more ambiguous: you would not necessarily be able to tell who is the bad one and who is the good one. One role is danced by a black ballerina and the other is danced by a white ballerina, and between them is an empty gold frame; the ballerinas do solos from Swan Lake, but they mirror each other’s movements, creating the illusion that one dancer is a reflection of the other. The way the piece is lit, it’s actually quite convincing as a reflection. Kim Brandstrup is the choreographer, and the dancers have done very beautifully. The interesting thing is that at some point they switch places so that the white ballerina is the reflection, and then it keeps going back and forth. And they do the dance twice. The pointe shoes and the tutus are made out of African textiles; I guess that’s part of my signature style. My proposal to the Opera House was that, rather than show the film of the ballet at the Africa Centre, they screen it outside in the summer where they usually show live footage of performances happening inside the Opera House so that members of the public can have free access. A lot of people show up for the screenings. This year they’ve got screens at Trafalgar Square and at a number of places around the country in various city squares, and my film will be run during the intermissions of live feeds from the Royal Opera House’s performances.

AD That ties in quite nicely with your Trojan Horse metaphor: it’s being quietly wheeled in, and the distinction between the two productions is minimal, but it’s there.

YS It becomes part of the so-called high art genre, if you like. You couldn’t really go higher than the Opera House, could you? I also like the fact that it’s outside, so a lot of people will see the work without having to be intimidated by the idea of going to the Royal Opera House or having to buy tickets.

AD Without even necessarily understanding the significance of what they are looking at, right? They are in Trafalgar Square watching a Royal Opera House ballet, and then suddenly during the intermission they are watching your film. Finally, what are you working on after this project?

YS I’ve got two shows coming up in New York in October, one at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum and one at the James Cohan Gallery. And after that I’m working on a major installation in Paris for 2007, for a new museum that’s just been built, called the Quai Branly. It’s an ethnographic museum, but they want to commission contemporary artists to do works there. It’s right by the Eiffel Tower, and it’s a big deal for the French; the prime minister is very involved. I’m working on a project called Garden of Love, where I’m creating a kind of French formal garden inside the museum; there will be fountains, and lovers taken from Fragonard paintings. Headless, of course. Filmwise there are other projects . . . but I’ll tell of those another time.

Yinka Shonibare BIO from art history.com

Yinka Shonibare's Age of Reason

by Beth S. Gersh-Nesic

Yinka Shonibare MBE calls himself a "postcolonial hybrid." Born in London in 1962 of Nigerian parents who moved back to Lagos when the artist was three, Shonibare has always straddled different identities, both national and physical. Son of an upper middle-class lawyer, he summered in London and Battersea, attended an exclusive boarding school in England at age sixteen (where much to his amusement he learned that his classmates assumed that all black people are poor), and enrolled in Byam Shaw School of Art, London (now part of Central Saint Martin's College of Art and Design) at age nineteen. One month into his art school studies he contracted a virus that rendered him paralyzed. After three years of physical therapy, Shonibare remains partially disabled.

These dual identities--African/British; physically able/challenged--are only two of Shonibare's acknowledged hybrid conditions. He knows that his name sounds feminine to the uninitiated, and his recently acquired title Yinka Shonibare MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) conjures up thoughts of exoticism, imperialism, globalization, and cultural confluence, just like his signature medium Dutch batik fabric.

Dutch wax fabrics, designed in the former-Dutch colony Indonesia and manufactured in Manchester, England, ended up as an export to Africa, thus inventing an "African" identity through fashion. "It's the fallacy of that signification that I like," Shonibare told Pernilla Holmes in 2002. "It's the way I view culture--it's an artificial construct." The intersection of European and African, colonizer and colonized, authentic and artificial, announces itself best through Shonibare's use and placement of this hybrid "African" cloth, especially because it is so theatrically seductive in Shonibare's elaborate installations. "I have always viewed art as a form of opera, or as being operatic," Shonibare explained in 2004. "And opera is excessive; it is beyond the real, and therefore hyper-real." For this 40-something member of the erstwhile yBa (Young British Artist) contingent, Dutch wax fabric (the real) fashioned into period Western dress (the hyper-real) encode tons of innuendo, or what the semiotic crowd calls "signifiers."

"The main preoccupation within my art education was the construction of signs as outlined in Roland Barthes's Mythologies," Shonibare elaborated in 2005. "So the idea of the theatrical for me is actually about art as the construction of a fiction, art as the biggest liar. What I want to suggest is that there is no such thing as a natural signifier, that the signifier is always constructed--in other words, that what you represent things with is a form of mythology."

Yinka Shonibare's most recent exhibition at James Cohan Gallery, Prospero's Monsters, enlists signifiers from three major works in art history: Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa (1819), Jacques-Louis David's Portrait of Antoine Lavoisier and his Wife (1788), and Francisco Goya's "The Sleep/Dream of Reason" from Los Caprichos (1799) to address contemporary issues. The name Prospero refers to the usurped Duke of Milan in William Shakespeare's play The Tempest (1610-11). He is a magician who causes a storm to shipwreck his traitorous brother Antonio and his crew on the island of Prospero's twelve-year exile. While Prospero's plight hinges on victimization, he in turn usurps the island and enslaves two inhabitants: Ariel and Caliban. Thus "Prospero's Monsters" refers to those who wrest power and those who are colonized.

Yinka Shonibare, MBE (British, b. 1962)

(Left)

La Méduse, 2008

Wood, foam, Plexiglas, Dutch wax-printed

fabric, and acrylic paint

83 1/2 x 66 x 54 in. (212.1 x 167.6 x 137.2 cm)

(Right)

La Méduse, 2008

C-print mounted on aluminum

Image size: 72 x 94 in. (182.9 x 238.8 cm)

Framed: 85 x 107 in. (215.9 x 271.8 cm)

Edition of 10

Image courtesy James Cohan Gallery

Art © 2008 Yinka Shonibare

In the first room of the exhibition, the theme of colonization and subjugation are underscored by a model of the famous, ill-fated French frigate Méduse (Medusa, in English), here outfitted with Dutch batik sails and menaced by an artificial wave. Next to this glass-enclosed diorama, an enormous C-print photograph of the miniature ship and tempest hangs on the wall.

The Méduse ran aground (like Antonio's ship in The Tempest) off the coast of Senegal (a former French colony) in 1816. However, in the actual event, the Méduse sailed into the treacherous shoals of the Arguin Bank, close to its destination. This tragic incident symbolized the dysfunctional Bourbon regime, restored in 1815 under Louis XVIII after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, in Théodore Géricault's gigantic painting The Raft of the Medusa. In recent appropriations of Géricault's masterpiece, Joel-Peter Witkin's Raft of the George W. Bush (2006) and Kara Walker's Post-Katrina Adrift (2007), re-activate the original's accusations: administrative negligence, human sacrifice and needless suffering. It seems that Shonibare joins his fellow artists in this reference to the Méduseas a signifier.

Théodore Géricault (French, 1791-1824)

The Raft of the Medusa, 1819

Oil on canvas

491 x 716 cm (193 5/16 x 281 7/8 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The story of the Méduse also brings to mind France's slave-trade, because the French governor of Senegal, who engaged in the ignominious enterprise, sailed on the ill-fated ship and survived on a rescue boat, while most of the crew perished on a jerry-built raft. Although slave trade was outlawed in France during the eighteenth-century, the French government turned a blind eye to the practice, allowing it to continue well into the nineteenth century.

References to the Méduse and The Tempest prepare the visitor to move into the main exhibition space which features five Enlightenment celebrities: mathematician Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier, Marquise de Châtelet, philosopher Immanuel Kant, economist Adam Smith, chemist Antoine Lavoisier, and encyclopedist Jean le Rond d'Alembert. Dark honey-colored headless mannequins, which nullify racial identification, are dressed in elegant eighteenth-century attire made of contrasting Dutch batik material. Each figure participates in a contemplative drama, its own tableau non-vivant.

Yinka Shonibare, MBE (British, b. 1962)

The Age of Enlightenment, 2008

(Left)

Adam Smith

Life-size fiberglass mannequin,

Dutch wax printed cotton, mixed media

Figure: 70 x 43 1/2 x 33 1/2 in. (177.8 x 110.5 x 85.1 cm)

Plinth: 59 x 67 x 5 in. (149.9 x 170.2 x 12.7 cm)

(Right foreground)

Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Life-size fiberglass mannequin,

Dutch wax printed cotton, mixed media

Figure: 65 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 30 in. (166.4 x 64.8 x 76.2 cm)

Plinth: 59 x 59 x 3 in. (149.9 x 149.9 x 7.6 cm)

(Right background)

Immanuel Kant

Life-size fiberglass mannequin,

Dutch wax printed cotton, mixed media

Figure: 29 1/2 x 41 x 31 1/2 in. (74.9 x 104.1 x 80 cm)

Plinth: 88 1/2 x 82 1/2 x 6 in. (224.8 x 209.6 x 15.2 cm)

Image courtesy James Cohan Gallery

Art © 2008 Yinka Shonibare

Moving from right to left in a counter-clockwise direction, we see the Marquise de Châtelet at her writing desk, one arm apparently a prosthesis; Immanuel Kant without legs at his writing desk; a hunched-back Adam Smith reaching for his volume The Wealth of Nations; Antoine Lavoisier sitting in an eighteenth-century wheel-chair positioned at his desk laden with reproductions of antique beakers and vials; and d'Alembert leaning on crutches against a lectern, writing in his notebook. Real books, measuring devices, inkwells and quills grace the surfaces of desks and bookcases, which are authentic, found reproductions or expressly crafted for the exhibition. Yet amid this meticulously rendered eighteenth-century calm, exuberant pinks, reds, blues and yellows in the colonist Dutch wax fabric pop out and agitate, injecting a healthy dose of realpolitik into an ersatz Neoclassical ideal.

Yinka Shonibare, MBE (British, b. 1962)

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Asia), 2008

C-print mounted on aluminum

Image size: 72 x 49 1/2 in. (182.9 x 125.7 cm)

Framed: 81 1/2 x 58 in. (207 x 147.3 cm)

Edition of 5

Image courtesy James Cohan Gallery

Art © 2008 Yinka Shonibare

The gallery's third room presents a summation of the first two rooms, by posing a question in five different appropriations of Francisco Goya's "El Sueño de la Razón Produce Monstruos" ("The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters," or "The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters"). Here, photographs of real people, clothed in costumes identical to the ones on view in the second room, re-enact the natty eighteenth-century sleeper encircled by owls, cats, bats, and other creepy creatures which explain the absent text: "Imagination deserted by reason, begets impossible monsters. United with reason, she is the mother of all arts, and the source of their wonders."

Shonibare's photographs ask in French: "Les songes de la raison produisent-ils les monstres en Afrique/en Amérique/en Asia/en Europe/en Australie?" ("Do the dreams of reason produce monsters in Africa/in America/in Asia/in Europe/in Australia?"). This translation seems to suggest that the imposition of the Enlightenment ideals may in fact create a few demons--such as dictators "democratically" voted into power.

It has been said that Yinka Shonibare's Prospero's Monsters is a "well-worn sermon preached to the converted." This comment pains me deeply. For I believe that Yinka Shonibare's still-life dramas effectively educate the public, increasing the likelihood that more people will be enlightened by his take on cultural history and the significant role of commerce. Moreover, Shonibare's decision to cast hybridism as the star of his shows produces some form of Reason, at least for now in the twenty-first century.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)